With special contributions by: Texas Slim, Clemenza, Mark Maraia and Colin Crossman

Thanks to Bitcoin Magazine giving my voice an outlet, throughout 2021, I have brought to your attention issues that I believe are plaguing the general health and well-being of the public. These include by way of diet and decision-making and how those effects are bleeding into the healthcare (doctors and nurses, but also health insurance) sectors, as well as education and the economy itself. Unfortunately, the problems don’t stop there — we need to follow in the footsteps of Alice and venture further down the rabbit hole.

The walls of this particular rabbit hole are structured with accountability and responsibility (check out my conversation with BTC Sessions where we briefly discuss this topic here).

America has been pushed from the pinnacle of learning, opportunity, and modern achievement into a corner of general deception and decay. One ought to ask: How did we get here? Well, let us consider the benefits — and consequences — of generations developing and proliferating across a period of history subsequent to America establishing a new world order with the IMF and World Bank via the Bretton Woods Agreement. The ease of life that followed in peacetime started at the peak of the power dynamic — politicians and bankers — thanks to global reserve status, and over the decades, has bled down through the socioeconomic hierarchies, across corporations, brick-and-mortar businesses, and eventually down to the average citizen — until the 1970s.

This easy lifestyle, enjoying the benefits of living from a position of leverage and power (thanks to the credit-based economy exacerbated by Nixon), has allowed complacency to flourish to extremely dangerous levels. Which, if we’re being completely honest, is easy to understand — just not easy to accept, nor identify when the consequences of such activity is not being felt to a significant extent that merits (or requires) reflection and rethinking.

Until now.

Ultimately, America’s political and economic woes can be seen quite easily by looking at the general public health crisis. We have been receiving the signals for decades, yet we continue to overlook and even ignore these warnings and notifications. By ignoring these omens, we risk following the very same path as great empires of history. If we do not act to re-route America’s health crisis, which encompasses both mental and physical health, then I fear that America’s time in the sun will end up resembling that of Icarus. These signals are most easily identifiable within our health industries, which include — but are not limited to — hospitals and medical practices, insurance and hospitality, fitness, food producers, diet and nutrition practices.

“The proper role of government, however, is that of partner with the farmer — never his master. By every possible means we must develop and promote that partnership — to the end that agriculture may continue to be a sound, enduring foundation for our economy and that farm living may be a profitable and satisfying experience.” — President Dwight D. Eisenhower, special message to the Congress on Agriculture, September 1, 1956

Civilizations And Health

David Montgomery is not a household name, but I believe that will change over the coming years and decades. As America continues down a path of economic hardship, thanks to the unraveling of our Keynesian economic system due to such liberal monetary policy and protectionist measures of propping up nonproductive corporate ventures … trouble is brewing just outside of our sight picture.

As I’ve burrowed further and further down the Bitcoin rabbit hole over the past years, I’ve learned so much that I may have actually developed an addiction. What started with investing strategies and economics has led to further investigations in my own particular field, health, the money behind much of the “health sector,” and recently to where our health comes from. That would be nutrition, yes, but following first principles thinking (FPT), we come to the real genesis — farming and its bedfellows, ranching and animal husbandry.

Of particular note to me would be the relationship of agriculture and the health of a civilization, especially in the death throes of empires across the ages. Montgomery covers this briefly in his publication, “Growing a Revolution.” Montgomery goes on to describe this revolution within farming against modern agricultural practices (much like there’s a rebellion occurring within economic circles, doubting Keynesian efficacy and seeking out different/better solutions, like bitcoin). You see, one problem that Montgomery uncovered along his journey was a relationship that I had not heard expounded upon before.

While the inflation angle is talked about religiously, pointing to the “why” a particular empire imploded upon itself, the food is rarely talked about as the final straw. I’m talking about the straw, you know … the one that “broke the camel’s back?”

A societal collapse of historical importance can ultimately be boiled down to one very simple (but priceless) variable that any community requires: the provision of consistent food production. Whether we’re talking about the first communities that had begun cultivating crops some 12,000 years ago, or we’re discussing active revolution from under a ruling power, the driver(s) of revolt end up disrupting the food supply. Rome and Paris both had this pressure point in common: bread shortages sparked public outrage. But what ultimately led to these shortages? Was it greed by the farmers? Could they have been extorting prices of crops due to a monetary landscape that was producing hardship? Or was it, perhaps, gluttony by the citizenry? Driven by an insatiable hunger of an entitled populace that grew up during an age of plenty and relative comfort.

Health And Food Sourcing

In reality, it was neither of these. What Montgomery describes on multiple occasions throughout his book is a series of events in history that don’t technically repeat, but they certainly do rhyme. Where an empire reaches peak power, actual growth stagnates. The ruling class attempts to push growth further by manufacturing (fabricating) it through inflationary monetary policies that eventually bleed into aggressive and destructive agricultural and harvesting practices. In the search for yield, these societies end up turning to strategies that sacrifice soil longevity and health. Eventually reaching a tipping point, where the soil can no longer support the desired output. These observations have even been highlighted by great philosophers of antiquity, like Plato and Aristotle who identified this relationship of agrarian techniques and rapid topsoil erosion.

Talk about a rabbit hole, huh? I mean, this is a problem that has been a problem since the first nomads decided to settle and sow what would become the seeds of farming strategies that would last across the ages. And we’re still doing it, just with greater technology and some improvements on understanding. Yet, we’re still making big mistakes.

Which can also mean we’re driving the issue faster.

As we’ve been discussing and learning about the economics that our modern society machinates, the very obvious connection that I, personally, began to ponder was the effects of modern economic and monetary policies upon public health. I often found myself asking, “If our economy is so great, and we’re ‘the greatest country in the world,’ why is it that we have some of the worst education ratings and health demographics on the planet?” This led me to a level of outrage that fueled a string of articles starting with this one. This article sparked up conversations with multiple great minds in the Bitcoin space, one of particular note that I want to bring to focus occurred between myself and Texas Slim.

Slim is doing some fascinating work, but of specific relevance to our journey today is his substack and the recent work that Clemenza has put together for Slim. Clemenza poetically happened to publish this work with Slim in parallel to my reading through Montgomery, and I honestly had to do a mental double take, not to mention pinch myself. Could it be that I was going down this journey at a literal perfect time to also come across Slim and Clemenza’s work? Clemenza provides a framing that really knocked me on my ass here:

“Have you connected the dots? Not only are our food processing practices providing poor nutrient density and non-bioavailable sources, but the natural sources we are growing are lacking 87% of the nutrients and vitamins as those that our grandparents grew up on. How much more obvious does it need to become that our legitimate pandemic of health is not just from poor physical activity but also with regards to our food sources? But this isn’t even the scary part guys….”

The scary part? Our soil health is even worse.

Montgomery goes on to write about the 2015 Agricultural Organizational Report, where it was stated that “soil degradation erodes global crop capacity by 0.05% per year.” On top of this, a third of the world’s agricultural land has been eroded. Going even further, despite heavy agro-chemical use by Western nations, up to 40% of global crop yields are lost to pests and disease. And then, down the line after said crops have been collected, ~25% of what is not lost to pests or disease gets wasted between production and consumption. Meaning that when it’s all said and done, we’re only capturing ~45% of the food we’re producing.

I can feel the tension building in you from here … but there’s more gas to throw on this specific fire. Particularly around an industry that gets overlooked, rather aggressively, fertilizers.

“Most people fail to realize that the lack of nourishment in our food today comes from the farming practices draining our soil’s richness. Let’s take oranges, for example. Today, we need to eat eight oranges to get our grandparents’ same nutrients from one. Nutrient degradation in our soil poses a severe threat to our ability to feed 9 billion people by the year 2050 in a way that promotes vitality and a healthy way of life.” — @cannoliclemenza, “We Are Overfed and Undernourished”

Addictions And Dealings

*(Did you do the math from that previous quote? Our fresh food is yielding ~12% of the foods of our grandparents’ time.)

The fertilizer industry is fascinating. Did you know that plants require nitrogen to grow, yet they cannot utilize the nitrogen gas that dominates our air? This is because nitrogen gas is extremely stable. So, the missing step in the equation was figuring out how to get nitrogen into the soil in order to stimulate growth in our crops.

How did we do it? Bombs.

…not that way….

During WWI, two scientists, by the names of Carl Bosch and Prince Harbor, devised a method to produce ammonia (NH3) from nitrogen gas while searching for a way to produce bombs that delivered a larger payload. However, after the end of WWII, bomb factories that were relied upon heavily for both global conflicts rapidly pivoted to fertilizer factories. Fast-forward around 50 or 60 years and we find ourselves looking at Koch Fertilizer and Cargill, which according to Montgomery (Chapter 4), are two entities that dominate the fertilizer industry.

Montgomery refers to Guy Swanson, a regenerative farmer, who analogizes the fertilizer industry to that of narcotics. He makes this comparison rather effective when likening the fertilizer industry to the negative feedback loop of drug addiction: Give a small appetizer of the product and get the prospect hooked off the immediate benefits, even though long-term use of the product will degrade health over time (whether this is out of ignorance or willful does not matter), which will drive the client back to the dealer as they seek a quick-fix remedy to the pains of their plight.

The problem? According to Montgomery’s work, only about 50% of nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers get taken up by soil. The rest gets carried away in the water table, ending up in our rivers, streams and oceans. Right next to the soil that gets eroded away by tillage. My own home state of Iowa has seen 50% of her native topsoil eroded away by this process since the days of the pioneers, with 30–40% of what is lost in recent history coming from gullies alone.

Look, I get it, this is all so boring and taking forever. It’s soil and fertilizer — not the best small-talk conversation around drinks. But, it is extremely important that we have this conversation and identify these problems. We can’t fix our shortcomings without first identifying them to begin with.

Why is this all so negatively impacting? Well, firstly we can start with asking, why do we fertilize soil to begin with? And then we can ask why are we addicted to fertilizer use?

“Burn down your cities and leave our farms, and your cities will spring up again as if by magic; but destroy our farms and the grass will grow in the streets of every city in the country.” — William Jennings Bryan

The Problem

We add fertilizer (herbicides and pesticides) to our soils in order to drive the growth of our cover crops so that we can capture the greatest crop yield and get one step further in progress toward solving the hunger problem. But this still begs the question, why do we need fertilizer?

Let’s pretend, for conversation’s sake, that we have a farm with absolutely perfect soil quality and climate. We may not need fertilizers for quite a while, but if we’re practicing modern farming techniques (aka, “extraction farming”), the soil will ultimately be degraded (because the nutrients have to come from the soil, and if those nutrients aren’t being replenished at an equitable rate then we get…) to the point of needing nutrient supplementation via fertilizers. The reason is a multifaceted flywheel.

First, the process of tilling breaks up the surface tension of the soil, destroying root systems, but also opening up the layers beneath to the extreme conditions of the open air. This can come in the form of intense rains that can carry away this newly exposed soil, or it can come in the form of direct sunlight and heat, which dries out the soil. But the heat doesn’t just dry the soil up, this heat also sterilizes the layers that have been newly exposed. This was emphasized by Rattan Lal (p.79, Montgomery), soil science PhD, and then confirmed when comparing temperatures of tilled farm soil temperatures to those of natural forests (a 20 degrees difference). Not only do tilled fields require more watering, but once soil temperature climbs above ~90 degrees Fahrenheit biological activity ceases. Meaning earthworms, root systems, and even the microscopic organisms that make up the mycorrhizal biome that produces the glucose that plant roots feed upon. This is where we finally arrive at the point.

How often do we think that our farmlands encounter summer days where the soil temperature approaches 90 degrees? I assure you that I do not have the answer, but growing up in Iowa … blistering hot days were quite common. When biological activity in soil stops, imagine it’s like stopping an entire economy for two weeks and thinking everything will be copasetic after. Okay, that was a half-joke. But seriously, the microbiome of soil is one of the most important systems to protect — without it, we’d all starve.

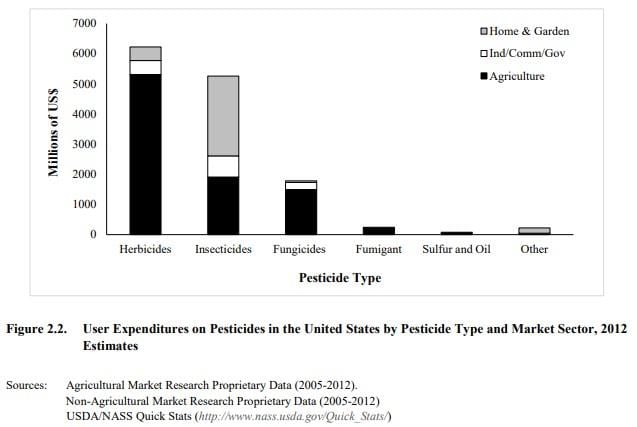

Yet this problem continues to get worse because, while the tilling alone is causing plenty of problems for the logistics of organic matter cultivation, we’re also dumping loads upon loads of herbicides and pesticides onto our fields. Even after engineering genetically modified crops (intended to be resistant to pests), pesticide use increased by 7% according to a 2012 study. So, by tilling fields we are increasing erosion, destroying biological activity that improves soil environment, weakening soil health, which is weakening the nutrient density of our crops, introducing herbicides/pesticides to our water sources (poisoning not just ourselves, but other food sources we consume), all of which is producing a negative feedback loop on the longevity and strength of the soil upon which we base our entire lives.

One of the very important dynamics of this agrarian system of relationships that is also heavily overlooked, (or rather, in my opinion, willfully ignored) is the relationship that livestock and ranching play in this very complex ecosystem. Movements like The Beef Initiative represent a return of classic, regenerative methods of understanding the source of our food and the access to high-quality beef.

“Standard feedlot cows are fed genetically modified (GMO) soy and corn which contain toxic herbicides and pesticides. Cattle also receive hormone therapy to assist in weight gain, which allows the cow to be sold at a faster rate. Unfortunately, at times, profit is a priority over quality when it comes to supply and demand. This is why it is so important to weaponize your health by obtaining high-quality beef from an organic or regenerative rancher. Today’s farmers and ranchers are strong examples of true conservationists. They have a deep love and appreciation for the land because it in turn supports their families.” — Texas Slim

Those animals also provide very important nutrients to the soil microbiome, of substantial note being nitrates and carbon. Nitrogen is that ever-important vitamin that we mentioned earlier that plants need but cannot pull from the atmosphere. They can pull carbon, luckily. However, carbon is a compound of high demand for life to flourish. There’s a lot of conversation going on around pulling carbon from the atmosphere, but very little being said around needing to get it back into our soil.

Without having a healthy and diverse ecosystem beneath the surface, our crops don’t grow as strong and healthy as we need them to, so that our children can grow strong and healthy, so they can grow up to be smarter and stronger than ourselves, in order to solve the bigger and badder problems that they will face long after we are gone.

What is the solution?

The Problem’s Problem

Now, the really, really fun part? The solution is one of a very similar structuring to that which is championed by the Bitcoin community: “Buy, and don’t sell,” but it is also more difficult than a single catchphrase.

We have to farm in a manner that is much more aligned with natural mechanisms. Not by trying to force Mother Nature via synthetic compounds, herbicides and pesticides. One thing that I have learned in my time in the health field: You don’t work against Mother Nature; she wins every time, you either work with her or fail.

The reason it’s difficult? The strategy requires a relatively complex scheduling of rotating cover crops between corn, soybean and wheat, as well as incorporating livestock rotations to provide manure for the fields. Very importantly, there is no tilling. By cutting out tilling, you maintain the surface tension of the root systems which act by protecting the microorganisms that dwell just below the surface of our planet. This ecosystem is extremely sensitive to exposure to the dynamics that come along with the open air, like temperature, weather and direct sunlight exposure, just to name a few. And even more important for the health of crops and soil diversity is that this wildly impactful mechanism provides very important nutrients to these plants that we need to nourish ourselves. If we want to answer why our populations are so unhealthy and weak, we have to look at why our foods are so unhealthy and weak … and if we are being honest with ourselves — which, right now, “we” are having a very, very hard time with being honest with ourselves — the next step along the FPT path leads us to the health of our soil.

What no-till farming ends up doing is attacking this worldwide problem on a slew of fronts. I’m talking about improvements in crop yields, fertilizer expenses, fuel expenses, water use, seed purchases (since GMO crops were supposed to reduce the need for fertilizers but actually increased the demand for more) and pesticides.

Time to run some numbers. Dwayne Beck, director of Dakota Lakes Research Farm (and first introduced in Montgomery’s book starting in Chapter 6), provides some statistics:

“Beck increased his soybean yields by 25 percent, from 63 bushels an acre to 79 bushels an acre. At the same time, corn yields increased as well, rising from 203 bushels an acre for continuous corn to 217 bushels an acre for a corn-soybean-rotation, and 235 bushels an acre for the more complex rotation, The whole system became more productive under a diversified rotation. And because it uses fewer inputs – less diesel, fertilizer, and herbicide – it’s even more profitable” (“Growing a Revolution,” p.106).

On Beck’s research farm they take all matters into consideration with their cover crop rotation studies, even so far as tire pressure — so as to avoid squeezing the water out of the soil, like a sponge. Oh, and with regards to that last claim of “requiring fewer inputs,” Beck also gives us this bit of data:

“An increase of organic matter content from 1 percent to 3 percent can double the soil’s water-holding capacity, while helping to prevent water logging that leads to the anaerobic conditions that favor soil-dwelling pathogens” (p.98).

To finish with one last bit of information as justification for any farmers that happen to read this long-winded piece of mine, this time coming from Dan Forgey, manager of Cronin Farms (20,000 acres comprising 40% cropped farmland and 60% native prairie pasture). Now, what Forgey is doing is much, much more complex. By incorporating a mixture of 10 different crops, he’s been working to improve organic matter and soil carbon on his lands:

“So far they’ve increased their soil carbon by 1 percent. That may not sound like a lot, but Forgey says that each percent of organic matter holds about $600 worth of nutrients an acre” (p.109).

Now we have to answer, “why do farmers choose to till then, if no-till is so much better?” Government subsidies. Remember my latest article, the one about the American education system? I mentioned in there how government subsidization (along with unionization) ultimately culminated into a parasitic relationship that produced a negative feedback loop. And in this article, I discussed how government support in Corporate America produced a parasitic relationship that produced a negative feedback loop. Oh, and then this article, where I discussed the corner that insurance companies have been backed into thanks to a witch’s brew concocted out of the bond market and the propping up of zombie companies. The problem is that our farmers are not in any better of a position, which really disheartens me.

If you’ve never met a generational, Midwestern farmer, these folks can be the most compassionate and effective individuals on the planet (and lively to boot). Our farmers have been constantly under pressure especially in the past 50 years. As was infamously put by Earl Butz in 1973 to “get big, or get out,” America’s Nixon administration made it quite clear that their desire was for America’s farmers to industrialize (and centralize) in the search for fast money. This can hardly be disputed when considering the USDA secretary’s words here in combination with Nixon’s cessation of the gold standard. Since then the farmer’s flywheel has been spinning faster and faster, allowing large farmers to rapidly expand and industrialize while their smaller neighbors are forced to either double down and grip the wheel harder, or risk being cast out. All the while, we are destroying generational livelihoods and our own country’s health in the same breath.

The Corn

Okay, we are finally to the point.

Bitcoin — where does it fit into this equation? Well, we just got done discussing how farmers in America got hit with a quick left and a hard, nasty right hook back in the 1970s. Bitcoin would’ve been a fantastic rope to fall back on then, unfortunately … it just wasn’t there. However, we have it today.

Our farmers need bitcoin now. Inflation is hitting every corner of the market: shipping, resources, fuel, maintenance, replacement parts, fertilizers, costs of labor … the list literally goes on and on. But farmers need more than just bitcoin, they need our patience and our willingness to have the conversation. We’ve discussed how beaten and bruised our farmers are from decades of abuse, and how little time or energy they can afford to sacrifice thanks to the hamster wheel that Nixon and Butz forced them into.

Farmers that benefit from Bitcoin’s average ~200% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) can utilize BTC as a cushion to fall back on for those wishing to take the risk of transitioning from industrial “power” farming to regenerative (or “restorative”) farming. Cutting the subsidized fiat umbilical can be a big and scary risk, I wouldn’t judge anyone that is wary.

Bitcoin as a “hard money that can’t be f***** with” allows for our farmers to store (or invest) funds that would otherwise have been risked in equities for profits, or even used as a hedge or insurance for their crops (Mother Nature has a way of using seasonal weather to test our farmers). Our farmers — and their families — are extremely sensitive to the health of our economy, and with how overvalued equities are, and the bond market going through an existential crisis … I would sleep better at night knowing that the literal backbone of our nation is well supported.

Bitcoin added to the balance sheets of insurance providers that farmers rely on could help ensure that they will be supported in the face of market chaos.

Bitcoin custodied by farmers, and their families, could protect them from fears of any possibilities of bail-ins or account freezes by banks. Recent examples in Lebanon and Turkey stand as grim reminders that these are very real possibilities for every citizen living under a government regime that is commanded by a central banking authority.

Bitcoin-supported small businesses, machinists and truck drivers could help ensure that food continues to be provided, in some measure, in the face of potential hyperinflationary scenarios. By having an economy that is supported by bitcoin (and Bitcoiners), we could provide a literal life raft to communities in the face of potentially catastrophic economic and transportation conditions. Just recently we got a great example of how bitcoin (and its community) is capable of supporting economic hardships far and above what current fiat systems (and their brigade of middlemen and rent-seekers) can provide. As the volcano near Tonga spewed enough gas and debris to blot out the sun (including cell and internet signals), donation wallets were generated and funds began to flow virtually immediately to provide support to the people in need.

Just to be clear, these strategies apply globally. There is nothing that I am saying that is excluding our friends in Africa, Central, or South America, the Middle East, Europe or Asia. Not to mention the large portion of food that is imported to America, we actually need our international friends and suppliers of food abroad to begin protecting themselves with bitcoin, as well as longevity solutions such as restorative farming practices. Bitcoin is a global phenomenon and stands to support any individual regardless of nation of birth, creed, race, political affiliation or net worth.

Bitcoin is about self-sovereignty. Restorative farming is about food sovereignty

Bitcoin is about self-preservation. So is healthy soil.

Bitcoin is about maintaining sustainability and longevity. So is healthy soil.

Bitcoin is about the best solution for every participant, especially if it’s the difficult one.

All of the above points encompass regenerative farming values, and lastly…

Regenerative (“restorative”) farming is proof of work.

“Because the solution challenges a century of conventional wisdom and powerful commercial interests, and requires a profound shift in how we think about and treat the least glamorous resource of all – the soil beneath our feet.” — David Montgomery, “Growing a Revolution.”

This is a guest post by Mike Hobart. Opinions expressed are entirely their own and do not necessarily reflect those of BTC Inc or Bitcoin Magazine.